Above: Curtis Hills, 27th Class Emerson Fellow.

Years ago, a buddy of mine and I worked as youth organizers with the Nollie Jenkins Family Center (NJFC), a social advocacy organization, in Lexington, Mississippi. We were the new kids on the block, so we wanted to make a name for ourselves and move up the organizing ladder. One day the executive director, Ellen Reddy, told us we would head their campaign to abolish corporal punishment inside the Holmes County School District. Although we worked together, my buddy and I took two different approaches to researching, creating outreach materials, and talking with students, school administrators, and community folk.

I relied solely on the data and other information I collected, never lending an eye to anything outside or opposing my scope of research. When I spoke to community members, I was Google in human form—only referencing scholarly articles and stating the facts. My buddy did the opposite. He made the research make sense to him. As he collected data, he was careful to make it relatable to both our peers and adults. As people would quickly lose interest in my spiel, they would smile and nod their heads with understanding and appreciation to his.

Since then, things have changed a little. I am no longer doing social advocacy work after school; I now do this work as a Hunger Fellow with Alabama Arise, a statewide nonprofit that understands people are not poor because they want to be but because of state policy decisions. I will never forget the shame and disconnectedness I felt that day in Lexington. It fuels my work at Arise, and what better time to showcase my innovative communication approaches than during a pandemic? On-the-ground organizing has come to a halt. We rely now more than ever on the advantages of technology. Face-to-face interaction is much less common. The world, for now, depends on the cyber atmosphere. That’s why I love my work at Arise. I get to create content that serves as a resource to those families who need assistance the most. Those factsheets I create have become more than just colorful graphics. Those documents I craft contain information that could be the difference between a child receiving a nutritious meal or experiencing hunger.

I currently work as the communications and outreach fellow with Arise. Lately, because of the COVID-19 Pandemic, Arise has focused much of their efforts to advocating for and informing Alabamians of resources and providing updates on legislation around food, housing, and income assistance. As their vision states, it is important to ensure “all people have resources and opportunities to reach their potential to live happy, productive lives, and each successive generation is ensured a secure and healthy future.” The COVID-19 pandemic is putting into perspective why organizations like Arise do the type of work they do. Jobs are scarce, evictions are rampant, and hunger, around the world is at an all-time high. For years, organizations like Arise have advocated for the rights of those disenfranchised by unjust policies. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) has proven to be a good resource amidst our current pandemic but should only serve as an emergency source of aid. There is a clear divide between the rich and poor, and COVID-19 has made it evident that folks deserve to be paid a livable wage. Many of our countrymen and women are risking their health and safety for jobs that pay $7.25 an hour. The work ethic is admirable; however, the politics are disturbing.

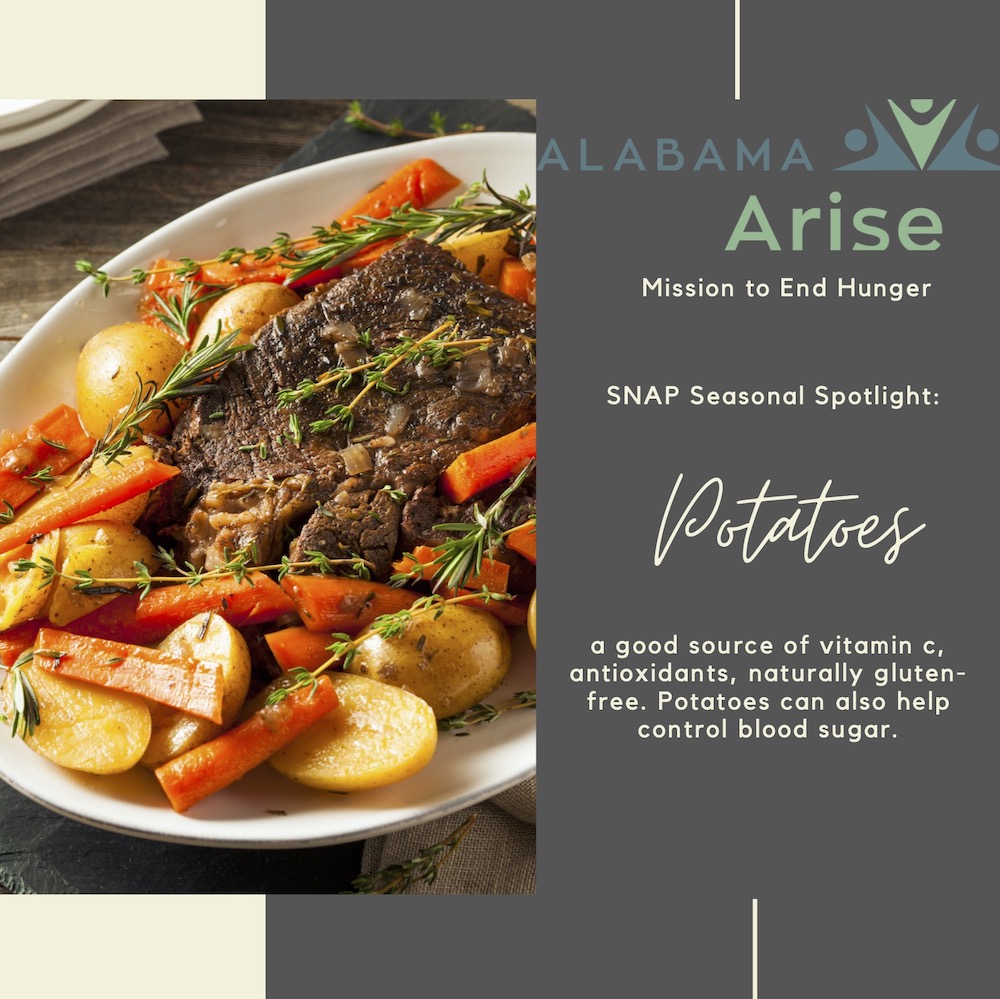

Recently, I was tasked with researching and creating hunger-related factsheets. Aside from drafting a compilation of documents that outlined the importance of the SNAP and school nutrition programs, I started a seasonal produce factsheet series. Each week, I highlight a healthy, affordable produce along with an example of a potential dish. The goal is to show folk how common foods like potatoes and carrots can turn into a large dish and relieve some of the pressure on household budgets stretched by COVID-19. To further ease people’s anxiety around the loss of employment or income, I have also created documents that highlight the benefits of programs such as Pandemic- Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT), the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), or the National School Lunch Program (NSLP).

Much has changed since my days as a youth organizer, but one thing has remained the same: the persistence of community-based organizations to work in the best interest of community people. The people of the United States have shown so much love and resilience for their fellow man and woman. From the blue-collar worker who was laid off but continues to volunteer at local food banks to the single mother who not only has to make every meal stretch, but also delivers produce boxes to the elderly in her community, they are the reason we are managing the journey of this pandemic. I am thankful that I get to aid in the fight by creating outreach materials for those who wouldn’t otherwise know of the resources allotted to them. No matter the legislation, we will remain united and strong. Keep going!

Special thanks to The Kroger Co. Foundation for their sponsorship of this placement of Emerson National Hunger Fellows in Alabama.

Special thanks to The Kroger Co. Foundation for their sponsorship of this placement of Emerson National Hunger Fellows in Alabama.

Below: a graphic highlighting seasonal produce created by Curtis for Alabama Arise.